Smell and Taste Treatment Research Foundation, Chicago, Illinois

Abstract: Folk wisdom has it that various aromas are sexually enticing but no data exists demonstrating actual effects of specific odors on arousal. The

present study reports the effects of 30 different scents on sexual arousal of 31 male volunteers by comparing their penile blood flow, measured b brachial penile index, while wearing scented masks and while wearing nonodorized, blank masks. Odors found generally pleasant in previous surveys were selected for this study. Each produced some increase in penile blood flow; the combined odor of lavender and pumpkin pie produced the greatest increase (40%). A multitude of mechanisms may mediate these effects. A potential application of odorants to increase penile blood flow in patients with vasculogenic impotence deserves study. Odors that may decrease penile blood flow have yet to be found for possible use in treating sexual deviants.

Key Words: Odors, Sexual Response

Introduction

Historically, certain smells have been considered aphrodisiacs, a subject of much folklore and pseudoscience. In the volcanic remnants of Pompeii, perfume jars were preserved in the chambers designed for sexual relations. Ancient Egyptians bathed with essential oils in preparation for assignations; Sumarians seduced their women with perfumes. A relationship between smell and sexual attraction is emphasized in traditional Chinese rituals, and virtually all cultures have used perfume in their marriage rites. In mythology, rose petals symbolized scent, and the work “deflowering” describes the initial act of sex. Farcical stock characters in the popular Italian Commedia dell’Arte of the Renaissance wore long-nose masks to symbolize their phallic endowment, a tradition that lingers in the figure of Punch. Dramatic literature abounds with sly references to nasal size as symbolic of phallic size, as in the famous play Cyrano De Bergerac.

Psychoanalysis has made much of these associations. Fliess, in his concept of the phallic nose, formally described an underlying link between the nose and the phallus.(1) Jungian psychology also connects odors and sex.

In the modern world the pervasive promoting and use of perfumes, colognes and after-shaves as romantic enticements have produced a multibillion dollar business.(2) And the popular arts as well have seized on the theme linking olfaction and sex. The movie Scent of a Woman portrays the importance of smell and sexual attraction in our society, as does the recent novel Perfumery.

The prominent connection between odors and sex among diverse historical periods and cultures implies a high level of evolutionary importance. Freud (3) suggested that odors are such strong inducers of sexual feelings that repression of smell sensations is necessary to civilization.

Anatomy bears out the link between smells and sex: the area of the brain through which we experience smells, the olfactory lobe, is part of the limbic system, the emotional brain (4), the area through which sexual thoughts and desires are derived. (5) Brill (6) suggests that people kiss to get their noses close together, so that they can smell each other (the Eskimo kiss). Or possibly they kiss to get their mouths together so they can taste each other since most of what we call taste is dependent upon olfaction.(7)

In discussing odors and sex we must begin with the birds and the bees. Classically, bees, moths, and other insects are known to release pheromones, aerosolized odorants that attract the opposite sex.(8) A female moth can release a pheromone into the air that attracts a male s far as a mile away, enhancing her changes of procreation. Similarly, pheromones exist throughout the animal kingdom in insect, subhuman primate, and primate genera (9) to the evolutionary benefit of the species. Whether human pheromones exist is unclear, but theoretic grounds support their presence, since structures that exist throughout the animal kingdom seem likely to be present in humans as well. Inside the human brain, near the top of the nose is an anatomical feature that gives us reason to believe that human pheromones exist: the vomeronasal organ. (10) Its function is unknown, but in subhuman primates, this is the area where pheromones act to increase the chance of procreation. This is where human vomeropherins bind. (11) (12)

When we exercise, we sweat through endocrine glands. (13) But when we are embarrassed or sexually excited, we sweat through apocrine glands that release high-density steroids (14) under the arms and around the genitalia; their role is unknown. In subhuman primates, the same apocrine glands release pheromones. (14) If these glands function similarly in humans, this might explain why when a woman raises her arms to her head exposing her axillae, her gesture is considered sexually provocative; “this charming grotto is full on intriguing surprises.” (13)

Physiologic evidence of the importance of odors in sexual excitation is two-fold: First, during sexual excitation, engorgement of the nose induces development of eddy currents (like small tornadoes). Then, since less of the air goes directly to the lungs (15), more pheromones or sexual attractants can reach the olfactory epithelium (16) and smell is more acute. Breathing from the mouth during sexual excitation is evidence of nasal engorgement and maximizes contact with stimulants and pheromones. Second, olfactory ability in women, generally better than that of men (16-19) is at its peak during ovulation, perhaps to detect any pheromones present. Increased olfactory ability at this time may explain why periovulatory women tend to have more sexual experiences. Possibly increased olfactory stimulation prompts an increase in sexual activity. (20)

Clinical observation supports the existence of pheromones in humans, as manifested by college roommate effect (21-22). Women who move into all-women’s dormitory halls have, by mid-term, synchronized their ovulating cycles with the other women in the hall. This indicates that a pheromone released by one woman may entrain the others in a pattern of dominance. The same phenomenon exists in small offices where women work together.

As further evidence of pheromones’ existence, male college students were asked to rate pictures of women while wearing masks either with no odor or with a postulated female pheromone (androsterone). The men with postulated female pheromone in their masks described the women as appearing friendlier and prettier than did those wearing unodorized masks (23).

During a study in England, a possible male pheromone was placed beneath certain desks in a classroom; then pictures were taken continually to monitor where students sat. Female students tended to sit near the desks where the postulated male pheromone was placed (24). Asked why they sat there, the girls said “it just seemed like the right place to sit.”

Pheromones may be not only sexual attractants, but also territorial markers, e.g., a dog establishes dominance in his yard by urinating there (25). In a study of a men’s college dormitory room, a postulated male pheromone was placed beneath specific toilet stalls which were then monitored (24). Men tended to avoid the stalls where the postulated male pheromone was placed, which seems suggestive that the scent had the effect of a territorial marker.

These experiments, of course, do not prove human pheromones exist. Yet perfume companies market their interpretations of pheromones, often containing musk, a pheromone of the male musk deer. Marilyn Miglan named a perfume “Pheromone,” however its scent is a floral mixture (26).

Various cultures favor various odors. In the U.S., women cut their axillary hair because this bodily smell is considered unclean. But in Eastern Europe, the smell is considered sexually provocative, and the axillary follicles are left virginal. Alex Comfort calls it the woman’s bouquet (27).

Medical evidence links smell and sexual response. In one study, over 17 percent of patients with olfactory deficits had developed a sexual dysfunction (28).

A relationship undoubtedly exists between the olfactory and sexual functions; its mechanism, however, remains to be discovered. In the present experiment, we investigate the impact of ambient olfactory stimuli upon sexual response in the human male.

Method

Participants

Subjects literate in English were recruited through solicitation on classic rock radio broadcasts. Thirty-one males, aged 18 to 6 years volunteered.

Measures

All subjects underwent olfactory testing with the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT), a 40 item, forced choice, scratch and sniff odor identification test (29) and the Chicago Smell Test, a three odorant detection and identification test (30-32). They were queried as to sexual preference, sexual practices, and odor hedonics.

During the experiment, subjects’ sexual arousal was determined using the brachial penile index (33) with the Floscope Ultra Pneumoplethymosgraph following manufacturer’s protocol (34). With this instrument, both penile and brachial blood pressures were measured and their ratio calculated, hence controlling for systemic effects. This allowed specific noninvasive assessment of penile blood flow.

Procedure

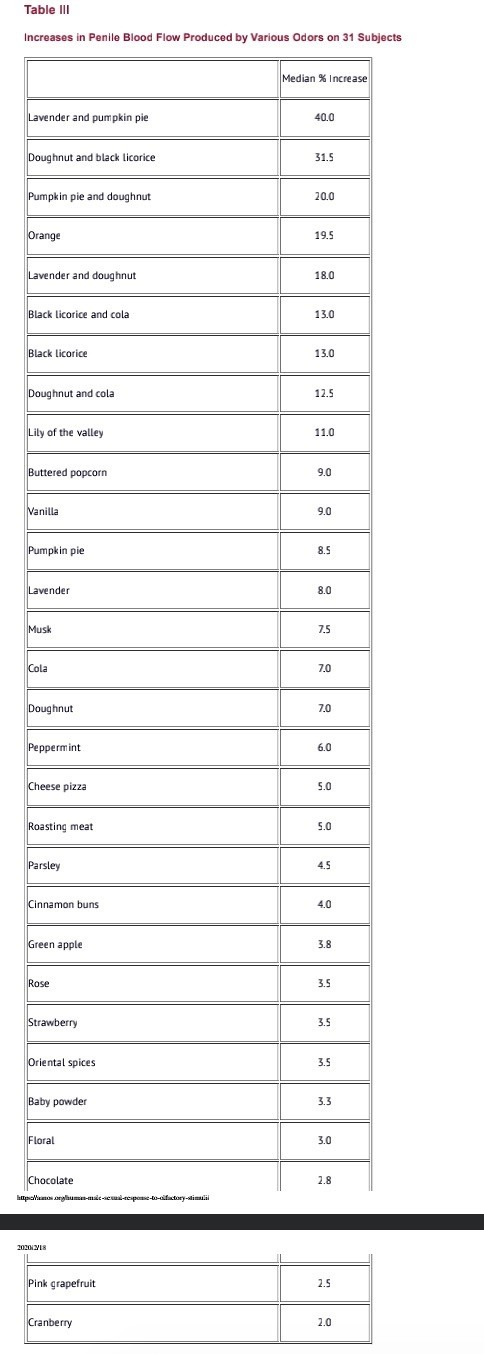

Twenty-four different odorants were chosen for this study based on their generally positive hedonics in previous surveys. In addition, 6 combinations of 2 of the most well-liked of these were chosen. The effects of the 30 odors on penile blood flow were assessed by comparing a subject’s brachial penile index while wearing an odorized mask to his average index while wearing an unodorized blank mask. This was done for each subject for each odor.

Subjects underwent assessment as follows: after being attached to the plethysmograph, three minutes were allowed for acclimation, then a blank control mask was applied for one minute and brachial penile index recorded. The blank mask was then removed and an odorized mask applied. Thus 30 odorized masks were randomly applied in double-blind fashion, with a three minute hiatus between masks to prevent habituation to the odors. Each mask was worn for one minute and brachial penile index recorded. Finally, an additional blank mask was applied for one minute and brachial penile index again recorded.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance is defined by a p value <=0.05. Data analysis includes these nonparametric tests: Signed Rank test, Wilcoxan Rank Sum test, and Spearman's Rank correlation coefficient (35-36).

Results

Results

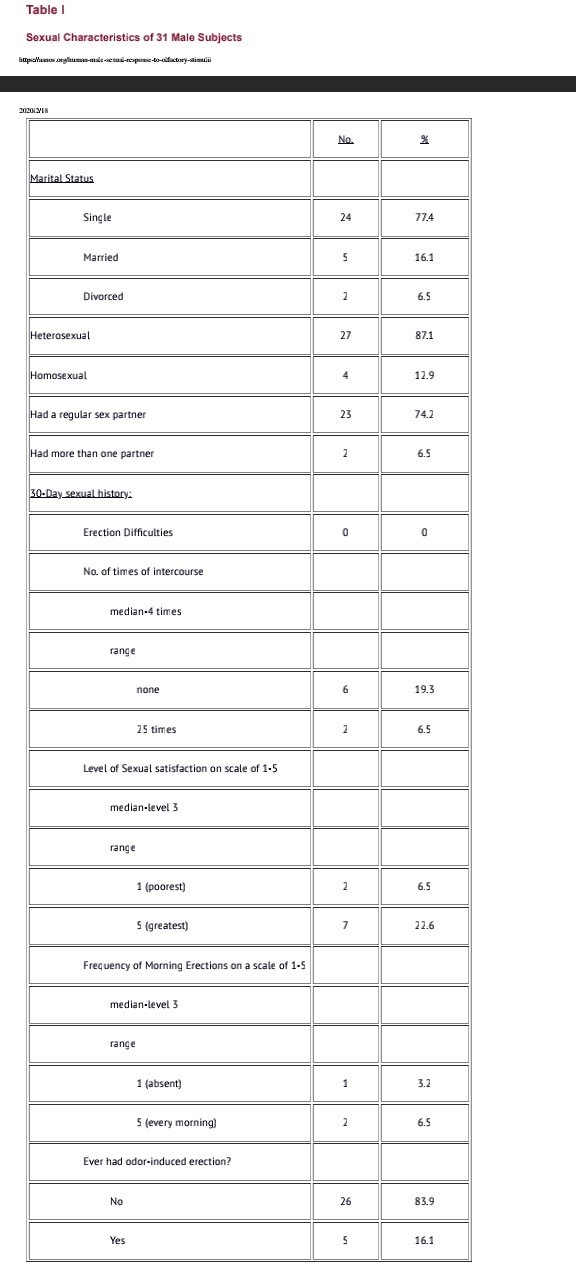

All subjects lived in Chicago or suburbs. Most (77%) were single and their mean age was 30 years, median 29 years with a range of 18 to 64 years. Most (87%) were heterosexual, had a regular sex partner (74%), had intercourse four times in the 30-day period just prior to the experiment and considered their sex lives fairly satisfactory (Table 1).

To assess their physiologic erectile function, subjects were asked to rate the frequency of their morning erections on a scale of 1 (absent) to 5 (every morning). Their median response was 3 (Table 1). Most (84%) stated that they had never experienced an odor-induced erection (Table 1).

Subjects’ olfactory characteristics are shown on Table II. UPSIT scores were graded based on published norms for age and sex. Given these, 52% of subjects scores were normal and 48% were microsmic, i.e., hyposmic (deficient in odor sensitivity) or anosmic (without a sense of smell). Over half the subjects (55%) had experienced odor-evoked recall, a phenomenon wherein an aroma triggers memories and associated feelings (37). More than half (61%) were nonsmokers. Most (71%) used cologne, and of those who had a regular sex partner, 83% of the partners used scent.

Effects of Odors on Penile Blood Flow

Each of the 30 odors produced an increase in penile blood flow (Table III). The combined odor of lavender and pumpkin pie had the greatest effect, increasing median penile-blood flow by 40%. Second in effectiveness was the combination of black licorice and doughnut, which increased the median penile-blood flow 31.5%. The combined odors of pumpkin pie and doughnut was third, with a 20% increase. Least stimulating was cranberry, which increased penile blood flow by 2%. None of the odors reduced penile-blood flow.

Men with below normal olfaction did not differ significantly from those with normal olfaction, nor did smokers differ significantly from nonsmokers. However, among subjects with normal olfactory ability, several correlations are significant: higher brachial penile indices correlate with greater age and with greater responses to the odor of vanilla (p=0.05); self-assessed level of sexual satisfaction correlates with greater responses to the odor of strawberry (p=0.05); and frequency of sexual intercourse correlates with greater responses to the odors of lavender (p=0.03), oriental spice (p=0.02) and cola (p=0.03).

Discussion

We hypothesized that hedonically positive odors, since they have other behavioral effects (38-40), would increase penile blood flow. Our data support this hypothesis.

A multitude of mechanisms exist by which this might occur. The odors could induce a Pavlovian conditioned response reminding subjects of their sexual partners or their favorite foods (41). Among persons raised in the United States, odors of baked goods are most apt to induce a state called olfactory-evoked recall (37). Possibly, odors in the current study evoked a nostalgic recall with an associated positive mood state that affected penile blood flow (38-40). Or the odors may simply be relaxing. In others studies, lavender, which increased alpha waves posteriorly, an effect associated with a relaxed state (42-43). In a condition of reduced anxiety, inhibitions may be removed and thus penile blood flow increased.

It has been shown that the odor of jasmine increases beta waves frontally, which is associated with alertness (42). Possibly odors may awaken the reticular activating system, making subjects more alert to any sexual cues, thus increasing penile blood flow.

Another possibility, odors may act neurophysiologically. MacLean (5) demonstrated that stimulation of the septal nucleus in the squirrel monkey induces erection. A direct pathway connects the olfactory bulb to the septal nucleus (44), hence, it seems anatomically correct that odor could impact upon the septal nucleus to induce erection with increased penile blood flow. This seems a strong possibility in our study, since the one subject who slept through the entire experiment showed the greatest increase in penile-blood flow in response to the combined odors of lavender and pumpkin pie.

We suspect a direct physiologic mechanism, yet we cannot rule out a possible impact of odors upon the dreams of the subject who slept through the experiment, perhaps with his dream content influencing penile blood flow.

Possibly odors can increase aggression, through septal nucleus stimulation. Increased penile-blood flow may be a measure of a “neighborhood effect” of induced aggression rather than direct sexual excitation (45).

Nor can we rule out a generalized parasympathetic effect, increasing penile blood flow rather than specific sexual excitation (46). As much as possible, we controlled for this by measuring brachial blood pressure coincident with penile blood flow.

The specific odors that affected penile blood flow in our experiment were primarily food odors. More directly, Rediwhip (c) has been used perigenitally, again indicating a strong relationship between sex, food and smell. Does this support the axiom that the way to a man’s heart (and sexual affection) is through his stomach? An evolutionary hypothesis explains why this may be so. After a successful hunt, humans in primitive tribes congregated around the food (47). There, perhaps they had most opportuni-ties to procreate. An increase in penile-blood flow in response to food odors, then would be an advantage. A recent finding about the Bonobos-that when they found a plentiful food source they stopped to have sex before they ate, perhaps to reduce quarreling over food-provides another explanation for the association between food and sex (48).

Humans can detect approximately 10,000 odors (8). Studies indicate that many of them affect behavior, i.e., certain floral smells can enhance learning (49) and buying behavior (50); green apple odor may ease claustrophobic feelings (51), barbecue smoke may induce a flight response (51) and inhaling certain food odors may help effect weight loss (52). Odors other than those examined in this study could possibly have a greater effect on penile-blood flow.

Olfactory sensation can influence the sexual reflex arc; as mentioned, human pheromones, which trigger sexual response through direct olfactory-limbic interconnections, are speculative (53-55). Penile erection, the measure of male sexual arousal (56) is a manifestation of outflow from the septal nuclei within the limbic system, and end organ for olfactory fibers (57). As a function of of the autonomic nervous system (58), penile engorgement is controlled by arterial flow through the pudendal artery and the smaller arteries to the penis. The first physical sign of sexual excitation is a change in penile-blood flow. Blood flow to the penis increases with sexual excitement and decreases with sexual inhibition (59).

We certainly cannot consider the odors in our experiment to be human pheromones, therefore we believe they acted through other pathways than do pheromones, which are thought to cause an endocrinologic effect upon the brain. A postulated pheromone, androstenol, a high-density steroid, is said to act very slowly on the endocrine system (60). Odors that affect penile-blood flow act immediately on the brain or have an immediate psychological effect, unlike the postulated pheromones.

These preliminary data suggest potential uses of odors as a treatment modality. Impotence, in 10-15% of cases, is organic, the most common cause being vaculogenic, usually due to diabetes (57-61). Current investigations should determine whether noninvasive treatment with odors can enhance penile blood flow in diabetes.

Although we found no odor to reduce penile blood flow, we hypothesized that such an odor might be found, possibly a trigeminal stimulant with a very negatively hedonic odor. Such an odor might be utilized to decrease penile blood flow in sex offenders, such as pedophiles, as part of their deconditioning or aversion training.

While we studied only male subjects, undoubtedly analogous odors might be found to affect women. Parallel studies of vaginal blood flow are being undertaken.

Refernces

1. Freud S. Report on my studies in Paris and Berlin (1886). Extracts from the Fleiss papers. Standard Edition, Vol. 1, London, Hogarth, 1892-99, 173-280

2. Dichter P. Second hand scents. Drug & Cosmetic Industry 1995; 156:72-75

3. Freud S. Civilization and Its Discontents (1930). In: Strachey J, (ed). Standard Edition, Vol. 21, London, Hogarth, 1961, 100

4. MacLean PD. Limbic system and its hippocampal formation: Studies in animals and their possible application to man. J. Neurosurg 1954; 11:29-44

5. MacLean PD. Cerebral evolution of emotion. In: Lewis M, Haviland JM (eds). Handbook of Emotions. New York, Guilford, 1993, 66-67

6. Brill AA. Sense of smell in the neuroses and psychoses. Psychonanalyt Quart 1932; 1:7-42

7. Hirsch AR. Smell and taste: how the culinary experts compare to the rest of us. Food Technology 1990; 44:96-102

8. Ackerman D. Natural history of the senses. New York, Random House, 1990, 5:26-27

9. Durden-Smith J, deSimone D. Sex and the brain. New York, Arbor House, 1983; 216

10. Moran DT, Monti-Bloch L, Stensaas LJ, Berliner DL. Structure and function of the human vomeronasal organ. In:Doty RL (ed). Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation. New York, Marcell Dekker, 1995, 794

11. Monti-Bloch L, Grosser BI. Effect of putative pheromones on the electrical activity of the human vomeronasal organ and olfactory epithelium. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 1991; 39:573-582

12. Monti-Bloch L, Jennings-White C, Dolberg DS, Berliner DL. Human vomeronasal system. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1994; 19:673-686

13. Gower DB, Nixon A, Mallet AI. Significance of odorous steriods in axillary odour. In: Van Toller S, Dodd GH (eds). Perfumery: Psychology and Biology of Fragrance. New York, Chapman and Hall, 1988, 47, 49

14. Russell MJ. Human olfactory communication. Nature 1976; 260:520-522

15. Schneider RA, Wolf S. Relatin of olfactory activity to nasal membrane function. J Appl Physiol 1960; 15:914-920

16. Parlee MB. Menstrual rhytms in sensory processes: Review of fluctuations in vision, olfaction, audition, taste, and touch.

17. Lanza DC, Clerico DM. Anatomy of the human nasal passages. In: Doty RL (ed). Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation. New York, Marcel Dekker, 1995, 53

18. Hirsch AR. Scentsation: Olfactory demographics and abnormalities. Internat J ARoma Ther 1992; 4:16-17

19. Deems DA, Doty RL. Age-related changes in the phenyl ethyl alcohol odor detection threshold. Trans Penn Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1987; 39:646-650

20. Adams DB, Gold AR, Burt AD. Rise is female-initiated sexual activity at ovulation and its suppression by oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med 1978;299:1145-1150

21. McClintock M. Menstrual synchrony and suppression. Nature 1979; 229:244-245

22. Graham CA, McGrew WC. Menstrual synchrony in female undergraduates living on a coeducational campus. Psychoneuroendocrino- logy 1980; 5:245-252

23. Kirk-Smith MD, Booth DA, Carroll D, Davies P. Human social attitudes affected by androstenol. Res Commun Psychol Psychiatr Behav 1978; 3:379-384

24. Gustavson AR, Dawson ME, Bonett DG. Androstenol, a putative human pheromone, affects human (Homo sapiens) male choice performance. J Comp Psychol 1987; 101:210-212

25. Ackerman D. Natural history of the senses. New York, Random House, 1990, 26

26. Moran J. Fabulous Fragrances. California, Crescent House, 1994, 183

27. Comfort A. Likelihood of human pheromones. Nature 1971; 230:432-433

28. Hirsch AR, Trannel TJ. Chemosensory dysfunction and psychiatric diagnoses. J Neurol Orthop Med Surg 1996; 17:25-30

29. Doty RL, Newhouse MG, Azzalina JD. Internal consistency and short-term test-retest reliability of the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. Chem Senses 1985; 10:297-300

30. Hirsch AR, Cain DR. Evaluation of the Chicago Smell Test in a normal population [Abstr.]. Chem Senses 1992; 17:642-643

31. Hirsch AR, Gotway MB. Validation of the Chicago Smell Test (CST) in subjective normosmic neurologic patients [Abstr.] Chem Senses 1993; 18:570-571

32. Hirsch AR, Gotway MB. Harris AT. Validation of the Chicago Smell Test (CST) in patients with subjective olfactory loss [Abstr.] Chem Senses 1993; 18:571

33. Laws DR, Pithers WD. Penile plethysmograph. In: Schwartz BK, Cellini HR (eds). Practitioner’s Guide to Treating the Incarcerated Male Sex Offender. Washington, DC, U.S. Department of Justice, National Institute of Corrections, 1988, 85-93

34. LifeSigns Corporation. PC Compatible FLOSCOPE ULTRA. Minneapolis, MN, Vascular Lab, 1994

35. Lehmann EL. Nonparametrics: Statistical Methods Based on Ranks. New York, Holden-Day, 1975

36. Colton T. Statistics in Medicine. Boston, MA, Little Brown, 1974

37. Hirsch AR, Nostalgia: neuropsychiatric understanding. Advances in Consumer Research 1992; 19:390-395

38. Warm JS, Dember WN, Parasuraman R. Effects of olfactory stimulation on performance and stress in a visual sustained-attention task. J Soc Cosmetic Chemists 1991; 42:119-210

39. Dunn C, Sleep J, Collett D. Sensing an improvement: Experimental study to evaluate the use of aromatherapy, massage, and periods of rest in an intensive care unit. J Advanced Nursing 1995; 21:34-40

40. Baron RA. Environmentally induced positive effect: Its impact on self-efficacy, task performance, negotiation, and conflict. J Appl Soc Psychol 1990; 20:368-384

41. Baron RA. Psychology 3rd ed. Boston, MA, Allyn and Bacon, 1995, 177

42. Sugano H. Effects of odors on mental function [Abstr.]. JASTS 1988; XXII:8

43. King JR. Anxiety reduction using fragrances. In: Van Toller S, Dodd GH (eds). Psychology and Biology of Fragrance. London, Chapman and Hall, 1988, 157-165

44. MacLean PD, Triune Concept of the Brain and Behavior. Toronto, University of Toronto, 1973, 14

45. Donatucci CD, Lue TF. Psysiology of penile tumescence. In: Hasmat AI, Das S (eds). Penis. Philadelphia, PA, Lea and Febiger, 1993, 19

46. Adams RD, Victor M. Principles of Neurology, 4th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1989, 418

46. Adams RD, Victor M. Principles of Neurology, 4th ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1989, 418

47. Diamond J. Third Chimpanzee: Evolution and Future of the Human Animal. New York, Harper Collins, 1992, 68

48. Blount BG. Issues in bonobo (pan paniscus) sexual behavior. American Anthropologist 1990; 92:702-714

49. Hirsch AR. Johnston LH. Odors and learning. J Neurol Orthop Med Surg 1996; 17:119-126

50. Hirsch AR, Gay . Effect of ambient olfactory stimuli on the evaluation of a common consumer product. Chem Senses 1991; 16:535

51. Hirsch AR, Odors and perception of room size [Abstr.]. 148th Annual Meeting Am Psychiatr Assoc, Miami, FL 1995

52. Hirsch AR, Gomez R. Weight reduction through inhalation of odorants. J Neurol Orthop Med Surg 1995; 16:28-31

53. Filsinger EE, Fabes RA. Odor communication, pheromones and human families. J Marriage and Family 1985; May, 349

54. Filsinger EE, Monte WC, Braun JJ, Linder DE. Human (homo sapiens) responses to the pig (sus scrofa) sex pheromone 5 alpha-androst-16-en-3-one, J Comp Psychol 1984; 98:219-222

55. Kirk-Smith M, Booth DA, Carroll D, Davies P. Human social attitudes affected by androstenol. Research Communications in Psychology, Psychiatry, and Behavior 1978; 3:379-381

56. Hirsch MS, Melman A. Overview of evaluation of impotence. In: Hashmat AI, Das S. (eds.). Penis. Philadelphia, PA, Lea and Febiger, 1993, 129-153

57. Kolodny RC, Masters WH, Johnson VE. Textbook of Sexual Medicine. Boston, MA, Little Brown, 1979, 10-11, 507-508

58. Cayaffa JJ. Rhinencephalon and the limbic system. Lecture notes: Cook County School of Medicine Basic Review Course 1981

59. Weiss MD, Physiology of human penile erection. Ana Int Med 1972; 76:793-799

60. Gustavson AR, Dawson ME, Bonett DG. Androstenol, a putative human pheromone, affects human (homo sapiens) male choice performance. J Comp Psychol 1987; 101:210-212

61. Pogach LM, Vaitukaitis JL. Endocrine disorders associated with erectile dysfunction. In: Krane RJ, Siroky MVB, Goldstein I (eds). Male Sexual Dysfunction. Boston, MA, Little Brown, 1983, 73

时间:2020-05-19 14:13:44

时间:2020-05-19 14:13:44  浏览量:3088 字号:

浏览量:3088 字号: